Is there a housing shortage in Durham?

Data indicates that the housing shortage impacting Durham is not from a lack of housing structures but rather an acute strain on housing affordability, according to a BCPI.OS investigation.

BCPI Open Sources leverages public data to help Durham residents better understand our city. This BCPI.OS article is written by Lucia Constantine with contributions from Chris Fedor.

Durham is in the midst of a building boom and a housing crisis, with construction continuing at record pace while low-income residents struggle to find an affordable place to live. If the city continues to attract wealthier newcomers and high-paying jobs, retaining affordability for long-time residents and low-income workers can become increasingly challenging, as evidenced by the recent City employee work stoppages and demands for fair and livable wages.

Traditional economic theory suggests increasing supply to meet demand will moderate pricing. Part of the theory is if new housing is continually built, even if it is expensive, older homes eventually “filter down” and become more affordable over time. Developers, city officials, and those advocating for broadly increasing housing supply (those who call themselves YIMBYs, or Yes In My Back Yard) alike agree with that logic and have promoted relaxing development regulations as a mechanism to boost supply.

But a look at existing data and industry reports suggests less of a shortage in supply and more of a mismatch in demand: residents who are in greatest need of housing are the least likely to be able to find it in their price range.

New constructions targets high end of the market; lower cost rentals disappear

Cities across the country are facing a shortage of housing due to underproduction but Durham is not one of them. A recent report by Up for Growth, a policy and research group focused on the housing shortage, found that the Durham-Chapel Hill metro area was one of 54 markets that adequately produced in 2012 and continued to meet or exceed housing needs in 2019. And while demand in Durham surged during the pandemic as people fled more costly cities or struck out on their own, the supply of housing has also steadily increased in the past decade with a record number of building permits issued in the past couple years.

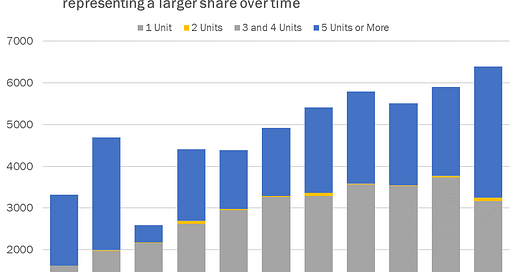

Although much of the growth has historically been driven by single family construction, multifamily construction has become a more significant driver in recent years. More than 4,900 multifamily units were under construction in 2023, with several new properties coming on line this year. One of those properties, Aura 509, recently opened on Mangum Street near downtown. With 182 units averaging less than 800 square feet, the building currently has 92 units available for rent on Zillow, with the cheapest one, a 613 square foot studio, starting at $1,430 per month. Aura 509 is not the only development showing vacancies. Renters looking for apartments in the $1,400 - $2,500 range have a lot of options in new buildings around downtown.

Between 2017 and 2022, the city saw a 61% increase in the number of units with rents above $1,000 per month and a 58% decrease in those under $1,000 per month. Nearly half of all units in 2017 rented below $1,000 but by 2022, only one in five rented for that amount. The loss of low-cost rentals in Durham leaves low-income families scrambling to find a safe and affordable place to live, especially near downtown. To afford $1,000 per month in rent, a household would need to earn at least $40,000 which is more than the average healthcare worker or childcare provider makes. As a result, nearly half of Durham renters are cost-burdened, meaning they are paying more than a third of their income in rent.

Meanwhile, an increasing number of those higher-end apartments are sitting empty. In a presentation to City Council, the Triangle Apartment Association, the trade group that represents the multifamily rental housing industry, reported an 8% vacancy rate in rentals as of May 2023 that was forecast to rise as high as 10% by 2025, meaning one in ten rental apartments in Durham are projected to be vacant in less than two years. By comparison, the industry considers a 3% vacancy rate to be healthy, while more than 4% means there is more housing than demand. According to Census data, the vacancy rate for the city has been 7% for the past several years with 9,887 vacant homes reported in 2022. Homes are vacant for different reasons whether it’s natural turnover, transition to short-term rentals such as Airbnb, idle investment holding or disrepair. In any case, vacant homes are an underutilized part of housing inventory.

As Durham’s population becomes wealthier, low-income residents have fewer housing options

Durham’s population has grown 22% in the last decade with the number of households increasing by 25%. Housing units also increased by 25% over that same time period. In 2022, Durham had 124,536 households and 134,423 housing units, roughly 1.1 units per household. The pandemic fueled new household formation, with more people wanting more space, especially a place to own. The number of housing units occupied by single person households increased 17% between 2019 and 2022, with 35% of all units occupied by single person households, more than any other household size.

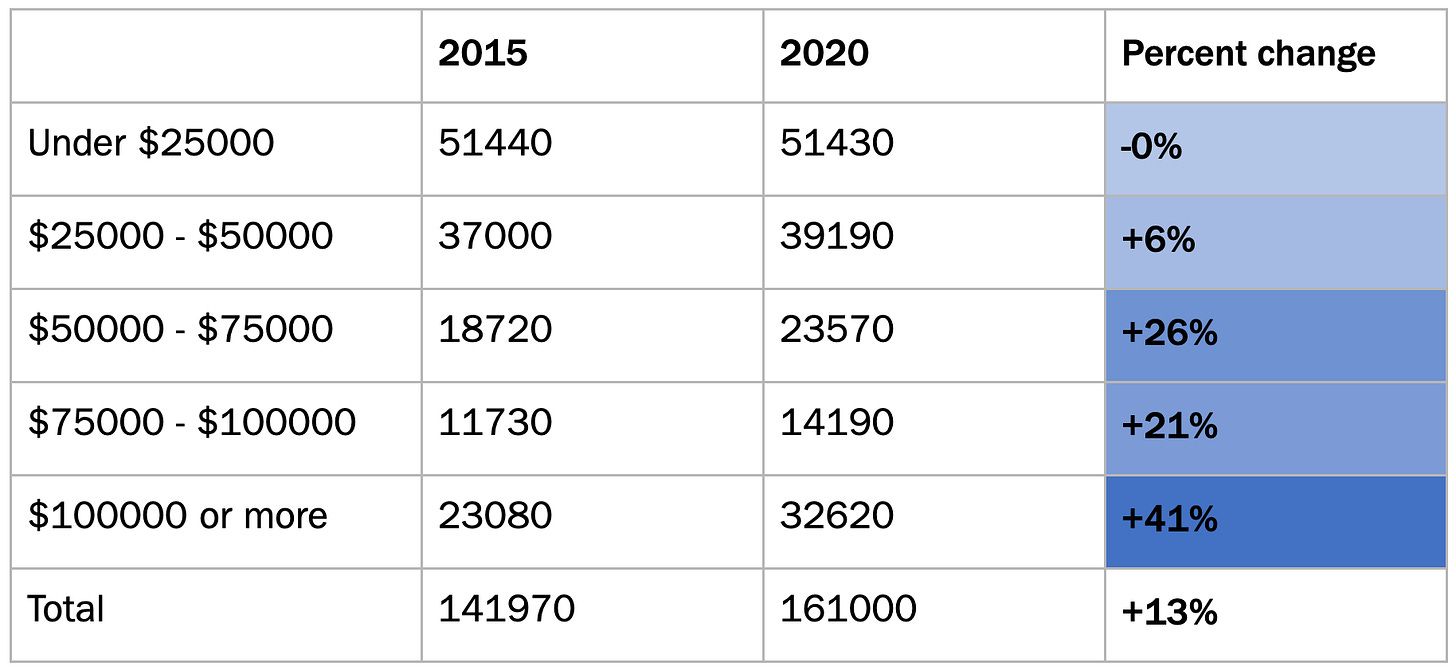

New people are moving to Durham but existing residents are also leaving. IRS data shows the number of tax returns filed in each county, as well as the movement between counties. Between 2020 and 2021, the number of tax returns leaving Durham was 14,865 and the number of those moving to Durham was 14,477, representing a loss of 2,568 people according to the IRS. At the same time, the number of filers in the highest tax brackets are increasing while those in lower tax brackets are decreasing suggesting a shift toward wealthier residents as lower income residents move away.

Tax returns in the highest brackets have seen the greatest increase

Wealthier residents have greater purchasing power and therefore, greater choice over what housing they live in. Some may opt for luxury rentals while others may settle for more modestly priced homes. Building more units at the high end of the market presupposes that these households will move up into more expensive units leaving more modestly priced units available. But as the vacancy data show, that has not been the case in Durham’s housing market.

Meanwhile, low-income households have very little choice. Data from HUD show that in 2019 there were 12,370 renter households earning below 30% area median income, roughly $20,000, and only 5,810 rental units affordable to households at that income range, resulting in a gap of 6,920. Current government support for housing only does so much. Of the 1,600 affordable rental units projected by the $95M housing bond passed in 2019, only 160 have been built. It can take years—twenty-three months on average—for households to receive a housing voucher to help offset the cost of rent and even then many landlords won’t accept them. And waiting lists for public housing take even longer with the average person waiting around 3 years for a unit.

Durham does have a significant shortage of both naturally occurring and subsidized affordable housing for its low-income residents. It’s unclear how relaxing zoning restrictions will change that, unless it’s accompanied with significant financial and policy commitments. It is clear that Durham’s recent development trajectory has prioritized housing at the high-end of the housing market for newcomers.

Thanks to you citizen journalists for digging up this info and explaining what’s really happening in Durham. Were these crucial points ever presented to or discussed by the City Council? If no, there should be no vote on SCAD until the members have thoroughly understood it. The N&O, Herald-Sun or WRAL ought to be doing the journalism work of presenting this most important info to the public. The incredible shrinking of local media leads to a blackout on public knowledge. That’s why City Council is about to vote for SCAD, against the wishes and interests of most of us. This will speed up the pace of lower-income people being forced to leave Durham — and their relatives, friends, jobs, support systems, and the places they love.