BCPI.OS: Durham property tax burden became heavier on lower-wealth neighborhoods

A detailed geospatial analysis of the 2019 property tax reappraisals finds that change in tax burden was influenced by neighborhood boundary and inversely related with neighborhood wealth.

This BCPI: Open Sources (BCPI.OS) article is written by Chris Fedor and Lucia Constantine.

Last month Durham elected a new mayor and three city council members. Now that they have taken office at last week’s Council meeting, they will have to come together to govern a city of distinct contrasts. A city proud of its newly expanded HEART program but struggling to answer emergency 911 calls. A city with a lot of new development and presumably tax revenue but whose essential city employees have fought repeatedly for cost of living adjustments to their pay and struggle with widespread understaffing.

When the Durham sanitation workers went on strike earlier this fall in response to these tensions, their campaign received widespread community support, perhaps driven by these diverging perspectives on the state of the city. How can a city undergoing such a transformative real estate boom proclaim poverty when it comes to adequately providing basic and essential services? How can the expectations of the citizens be so mismatched with the perceived abilities of the city to deliver?

Part of the answer to that question may have its root in the property tax reappraisals of 2019. BCPI: Open Sources looked at the community’s property tax record to better understand the its largest source of revenue.

In the 2022-2023 budget, property taxes generated an estimated $125 million dollar (49%) towards the city’s General Fund and an additional $67 million (84%) towards the city’s Debt and Solid Waste funds. The amount of revenue generated by property taxes can be modified in two ways: it can either change via a tax rate modification or from changes in the underlying land and improvement values.

In 2019, Durham underwent its most recent county-wide general tax reappraisal. The goal of this reappraisal was to “reset all real property tax values to current market value” and one is required to be done at least every eight years. (Durham has its next reappraisal scheduled for 2025 and has committed to beginning a four-year cycle of reappraisals after that. Also of note, the County manages the Tax Administration Office which conducts appraisals; the City and County then separately set their own tax rates to fund their respective operations.)

By comparing the tax records between 2018 and 2022, it is possible to estimate both total and percentage increase in property tax valuations from the 2019 reappraisal for the approximately 100,000 individual tax parcels that make up this county.

This analysis only includes parcels whose last known sale date was prior to January 1, 2017. To further minimize the influence that structural improvements might have on the value, any parcel associated with a building permit after January 1, 2020 was excluded. In this way, BCPI.OS seeks to understand how identical structures were re-valued due only to overarching “market conditions.”

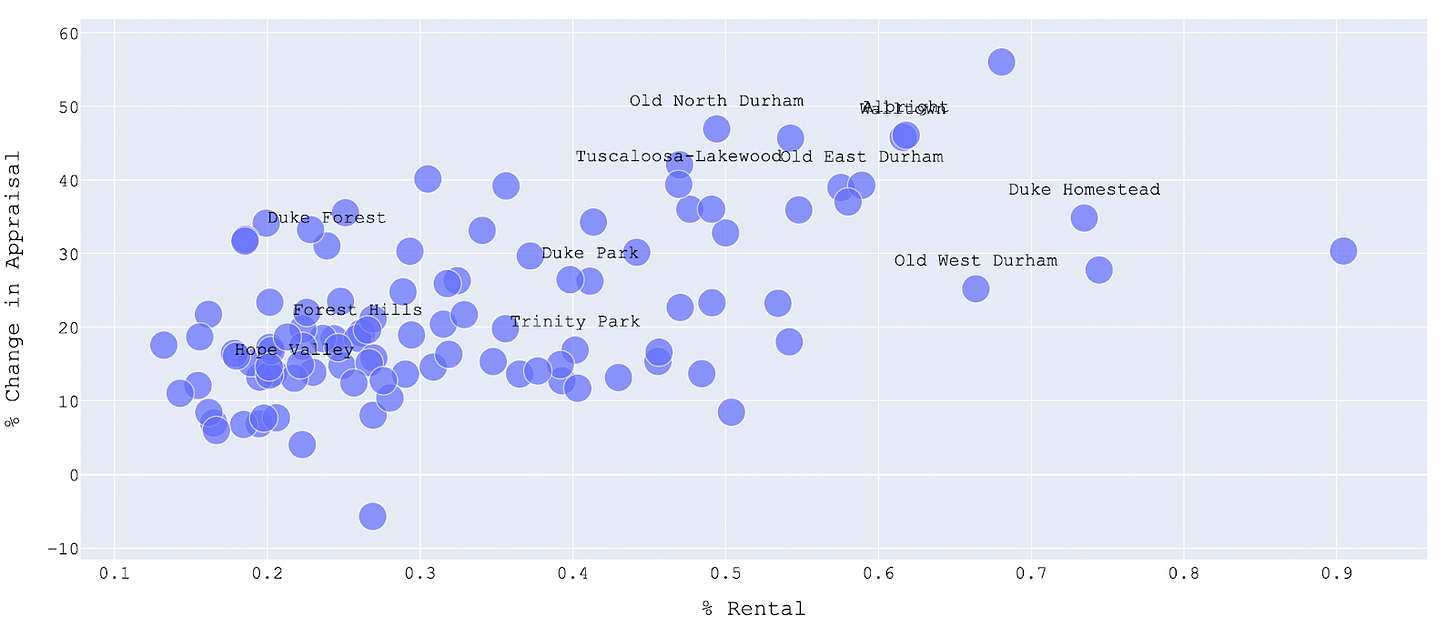

The median increase in the approximately 85,000 eligible property valuations after 2019 was approximately 20%. Of the neighborhoods represented by point locations in the below scatter plot, Colony Woods experienced the smallest median change at 4%, while Lyon Park saw the largest median increase at 57%.

Of the 24 available neighborhoods with a median home value exceeding $300,000, only four (17%) experienced a tax valuation increase at or above 20%. Of the 80 remaining neighborhoods with a median property value below $300,000, 42 of them (53%) saw their tax valuation increase by more than 20%.

For example, the scatter plot above shows that after 2019, the Trinity Park neighborhood (in the bottom right quadrant) had a median assessed home valuation of $392,000. This represents an estimated 16% median increase from the previous tax valuation. Meanwhile, the Albright neighborhood (in the upper left quadrant), with a median home assessment of $142,000, experienced a 46% increase in their property tax valuation as a result of the 2019 reappraisal.

Homeowners in Albright, Walltown, East Durham, or Colonial Village, saw their property tax valuations go up on average close to 40%. Meanwhile, property valuations in Trinity Park and Forest Hills increased by approximately 15%. The wealth differential of these neighborhoods as expressed by home values is anticipated to mean longtime homeowners in neighborhoods like Walltown are more likely to struggle to afford their significantly higher property tax bills than those in neighboring Trinity Park who experienced on average much smaller tax increases.

Increases in property taxes do not only impact homeowners. The majority of landlords pass on the price of a property tax increase to their tenants via an increase in rent. BCPI.OS roughly estimated the percentage of rental units by identifying any parcel whose owner's mailing address differs from the parcel's physical address. The below scatter plot indicates that neighborhoods that saw a large increase in median tax appraisal, also tended to have proportionally higher density of rentals. As such, renters who do not benefit from real estate price-based wealth building would likely have been disproportionately impacted by this reappraisal.

A change in property tax valuations does not exactly equate to a change in property taxes paid. The city can (and often does) reduce the overall property tax rate in conjunction with the reappraisal. For example, in the 2017-2018 budget the general fund levied a 33.99 cent tax rate compared to the 31.55 cents of the 2022-2023 budget. However, since that is a flat rate applied across the city, the change in valuation does constitute a direct change in relative tax burden of these neighborhoods.

The differential impacts of the tax reappraisal on people’s pockets also inform their expectations of what the City should provide.

The average longtime resident of Walltown, for instance, facing a significant increase in their taxes or rent, might expect a comparable increase in the quality and availability of city services, infrastructure, and programming. They are left asking where their money is going without clear answers. Meanwhile, the average longtime resident of Trinity Park, paying a much more modest overall tax change (or perhaps even a decrease based on a rate reduction), might be very satisfied with what they have experienced.

Unless they choose to change the tax rate, the new city council will have to try to bridge the diverging expectations of its citizens using the limited revenues that they have. With the next mass reappraisal scheduled to occur in 2025, it will likely open yet another front in which a burgeoning city will need to continue wrestling with questions of wealth and equity.

Delighted to see this piece asking some basic questions that one would have thought every citizen asked before going to the polling booth this November. But I'm afraid they did not. That many of our poorest neighborhoods are the places that have been raped and gentrified most egregiously is no surprise. Values have quadrupled, or more, in some places, whereas traditionally high value neighborhoods have not seen that kind of value increase - and that accounts for some of the disproportion in the burden. What is perhaps more pertinent is that when people have been in their homes for 20+ years, in a marginal neighborhood that has experienced unprecedented value hikes, they should be given some kind of tax break. And the city should be able to work that algorithm (it's really not complicated). Because the city DOES want to retrieve higher taxes from that new build in Walltown that just sold for $800k, but their neighbor in a modest home for decades shouldn't have to suffer for the gentrification of his neighborhood and be forced out of his home because of a tax burden that makes no sense. Despite our 'progressive' government, we have a punitive tax structure that fails to accommodate real people who don't fall into categories for federal poverty level.

I asked Leo Williams last April "where's the money" - tax revenue from the massive influx of development. He didn't know. We discussed for 30 minutes Durham's needs, especially housing. Mayor Williams made no apologies: "well, yeah, we're gonna have to raise taxes" he claimed, despite the huge gain to the coffers by development. The disconnect is startling.